Georgian Sacred Chants on the Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom by Georgian composer Zakaria Paliashvili (1871-1933) is a setting for large mixed chorus of a set of transcribed chants from the Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom, the most common Eucharistic service used in the Orthodox Church. Although individual sections of the work are known, it has remained basically unknown as a single work. The recording by the Capitol Hill Chorale in 2014 is the first in the Georgian language.

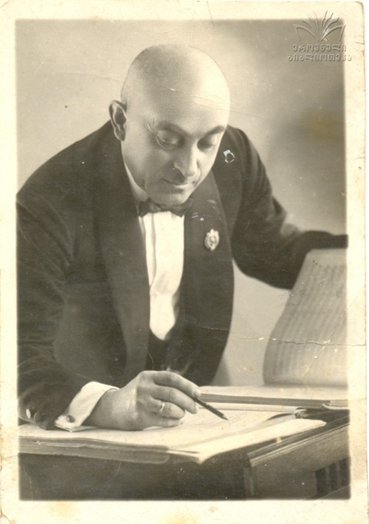

Zakaria Paliashvili (1871-1933) is a figure of national pride in Georgia, and is considered to be the father of Georgian classical music. He is most famous as the composer of two operas, Daisi and Abesalom da Eteri, that draw heavily from Georgia’s folk tradition. The music for Georgia’s national anthem was taken from these two operas. The opera house in Tbilisi, Georgia’s capital, is named for him, and he is buried on its grounds. His portrait appears on one of the bills of Georgian paper money. Yet he is little known in the West.

He grew up the third of eighteen children in Kutaisi, a small city in western Georgia, the son of amateur musicians active in the local Georgian Catholic Church. Several of the children were talented musically, and the family moved to Tbilisi where Zakaria and several of his siblings sang in the church choir and played organ. In 1891, Paliashvili entered the Tbilisi Music School, which was led at the time by the future famous Russian composer Mikhail Ippolitov-Ivanov (1859-1933). After graduating, Paliashvili spent 1900 to 1903 in Russia, studying at Moscow Conservatory, where Ippolitov-Ivanov was then a professor. Paliashvili’s main teacher was Sergei Taneyev, the teacher also of Paliashvili’s Russian contemporaries—Rachmaninoff, Scriabin, and Gretchaninoff. In 1903, Paliashvili returned to Tbilisi and began a career as conductor, teacher, ethnomusicologist, composer, and organizer of musical activities and institutions.

At the time Palishvili composed his Georgian Sacred Chants in 1909, Georgia had been part of the Russian Empire for more than 100 years. The Russian policy of “Russification” in place throughout the Empire had increasingly imperiled Georgian cultural traditions, including particularly Georgian chant, a unique form of 3-part liturgical singing in the Georgian Orthodox Church that had existed for more than 1,000 years, predating the emergence of polyphony in Western European music by several centuries. Facing this threat, Georgians had begun transcribing chants on paper to preserve what had previously been handed down orally by master chanters. Paliashvili chose to use as the basis for his “choralizations” the written chant transcriptions published in 1899 by Ippolitov-Ivanov, who was under a contract to leaders of the Georgian chant transcription movement.

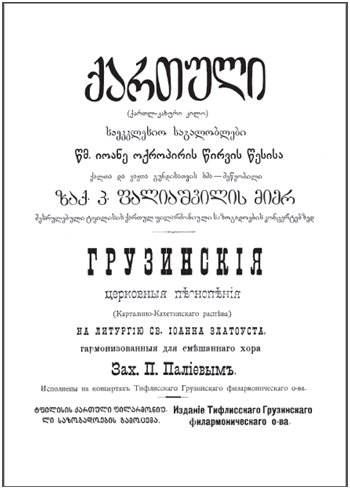

As a proud but non-Orthodox Georgian, Paliashvili’s choice of the Orthodox service as one of his first published compositions was noteworthy. Paliashvili makes clear in a Foreword that accompanies the published score that these settings were intended as his contribution to the preservation of this important aspect of Georgian musical culture. His nationalist intent is clear from the prominent size of the word “Georgian” on the title page.

However, Paliashvili set the text not only in Georgian but also Church Slavonic, the language of the Russian Orthodox Church, in order (as he writes in the Foreword) to spread awareness of Georgian chant among Russian audiences. In addition, instead of the 3 parts traditionally used in Georgian chant, Paliashvili used the 5, 6, and 7 parts for mixed voices he would have heard sung by Russian liturgical choirs in Moscow as a student at Moscow Conservatory. It was a controversial choice which elicited strong condemnation from Georgian traditionalists. In making his transcriptions, Ippolitov-Ivanov worked with two of the Karbelashvili brothers, priests from a family of master chanters from eastern Georgia, with whom Paliashvili also later became acquainted. The Karbelashvilis were outraged that the traditional Georgian 3-part transcriptions that Ippolitov-Ivanov did to preserve the oral tradition of their family were turned into 5- and 6-part choral arrangements by Paliashvili.

One can theorize that Paliashvili had several purposes in creating his setting of Georgian Sacred Chants. Clearly, the piece was meant as his contribution to the preservation of a Georgian musical heritage disrupted and threatened by Russian influence. Ironically, it may have also have been an effort by Paliashvili to make his professional contribution to the outpouring of chant-based liturgical writing going on in Russia, particularly Moscow, at the time, which included settings of the Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom by Ippolitov-Ivanov, Rachmaninoff and many others. One can theorize further that the piece may also be in effect, and perhaps unconsciously, an homage to Ippolitov-Ivanov, a man half a generation older than Paliashvili, whom Paliashvili apparently did not know well, but who served as a professional model and inspiration for the aspiring young Georgian musician and composer.

Too western for Georgian traditionalists, and too Georgian for the Russian Orthodox Church, by the time of the Russian revolution, the piece was obviously too religious for the Soviets. However, while copies of transcribed chant were aggressively suppressed and hidden away, Paliashvili’s settings (for example, his setting of Shen Khar Venakhi) were known and sung privately, often in reconstituted traditional 3-part settings of the “Paliashvili arrangements” by those interested in recreating traditional Georgian singing. In the 1950s and 1960s, this included the founder of Rustavi, an ensemble which subsequently played a major role in fostering an appreciation of traditional Georgian music internationally.

Thus, Paliashvili’s Georgian Sacred Chants may not have spread awareness of Georgian chant among his Georgian and Russian contemporaries as he had intended, but it did indirectly serve that goal to later generations.